You are here

Chapter 8. John 1:14 – “And the Word became flesh and tabernacled in us”

– Chapter 8 –

John 1:14: “And the Word became flesh and tabernacled in us”

We now look at John 1:14 which, when translated literally and accurately, effectively undermines trinitarianism. For convenience, we divide the verse into its three clauses, a, b, c:

John 1:14a

And the Word became flesh

John 1:14b

and dwelt among us,

John 1:14c

and we have seen his glory, glory as of the only Son from the Father, full of grace and truth.

We will look at 1:14b in this chapter, and 1:14a in the next chapter.

To interpret the whole verse properly, we will need to take into consideration the concept of the tabernacle and the temple. That is because the word “dwelt” in John 1:14b (“dwelt among us”) does not come from the common Greek word for “dwell” or “live” but from a special word which means “to tent in” or “to tabernacle in”.

Tabernacle and temple: a quick overview

The word tabernacle is not used in English except in a religious context. For this reason, it is a mysterious word to many, but it is really nothing more than a fancy or traditional word for “tent” (from Latin tabernaculum, “tent”). Hence we will use tent and tabernacle interchangeably. In the Old Testament, the English word tabernacle usually translates the Hebrew mishkan (“dwelling place”).

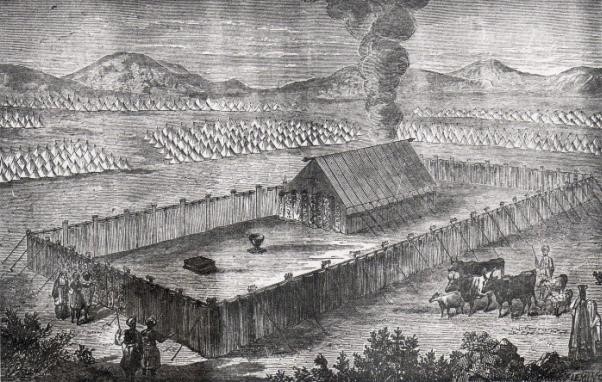

Here is a drawing of the tabernacle found in an 1891 German Bible. It shows the tabernacle being filled with God’s Shekinah glory. The word shekinah pertains to the dwelling or the settling of God’s glorious presence.

In the picture we see a courtyard surrounded by thousands of small tents arranged according to the 12 tribes of Israel. Inside the courtyard is the tabernacle itself, which in the Bible is also called the “tent of meeting”. All the objects seen in the picture — the tabernacle, the courtyard fixtures, the altars, the surrounding tents — can be dismantled and transported by the Israelites as they journey through the wilderness to the Promised Land.

The tent is further divided into two sections: the Holy Place and the Most Holy Place. The latter is the special dwelling of God’s Shekinah glory that descends upon the tabernacle and opens a way for God to meet with His people there (cf. “tent of meeting”). As seen in the picture, Yahweh’s glory appears as “a pillar of cloud by day and a pillar of fire by night” (Ex.13.22) that descends upon the tabernacle, filling it with His glory and presence: “Then the cloud covered the tent of meeting, and the glory of Yahweh filled the tabernacle.” (Ex.40:34)

Even before the tabernacle had come into being, God had already conceived it as His dwelling, for He had earlier said to Moses, “And let them make me a sanctuary, that I may dwell in their midst” (Ex.25:8).

Several centuries later, the tabernacle was replaced by the temple, for by then Israel had long settled in the Promised Land, and no longer needed the tent to be mobile. So the tent was replaced by a permanently settled structure, Solomon’s temple, also known as “the house of the Lord,” literally “the house of Yahweh” for it was Yahweh’s dwelling, as seen in the following passage (note the boldface):

… a cloud filled the house of Yahweh, so that the priests could not stand to minister because of the cloud, for the glory of Yahweh filled the house of Yahweh. Then Solomon said, “Yahweh has said that he would dwell in thick darkness. I have indeed built you an exalted house, a place for you to dwell in forever.” (1 Kings 8:10-13)

But a few verses later, Solomon laments that God’s presence is too vast to be confined in the temple: “Behold, heaven and the highest heaven cannot contain you; how much less this house that I have built!” (1Kings 8:27; cf. Acts 7:48)

Yet the infinite God, in His love and mercy, was pleased to dwell in the house built by His chosen people, the Israelites, and to fill it with His glory and presence.

Note: In English, tabernacle is a noun, not a verb, but Greek has both a verb form skēnoō (to tabernacle in) and a noun form skēnē (a tabernacle). BDAG says that the noun is used in the LXX of “Yahweh’s tabernacle”. Significantly, BDAG says that in John 1:14, the verb is “perhaps an expression of continuity with God’s ‘tenting’ in Israel”.

In John 1:14, “among us” is literally “in us” — a fact that undermines trinitarianism

The conventional translation of John 1:14b (“dwelt among us”) is defective on two counts, and in each case, an important Greek word is not being translated according to its principal or literal meaning. We have already mentioned the first case: In the original Greek text, the word “dwelt” does not come from the common Greek word for “dwell” or “live” but from a special word that means “to tabernacle in” or “to tent in”. This fact is well known and mentioned in many study Bibles.

But the second case is more significant because it undermines trinitarianism: The conventional rendering “among us” in John 1:14b (“dwelt among us”) is inadequate because the Greek has “in us”. The exact phrase in Greek is eskēnōsen en hēmin (“tented in us”) where en is the common Greek preposition for “in”. If the spelling of en looks familiar, it is because the English word “in” is derived from the Greek “en” via Latin “in” and Old English “in” (Oxford English Dictionary).

It is a plain fact that in John 1:14, “among us” is literally “in us,” as noted by people such as Raymond E. Brown, an eminent NT scholar.

Trinitarians reject “in us” even though it is the literal translation of en hēmin, and is lexically more probable than “among us”. It is striking that English Bibles, contrary to their usual practice, do not state in a footnote that in the Greek text of John 1:14, “among us” is literally “in us”; or at least state that “in us” is an alternative reading. Their silence may be an early hint that “in us” lends no support to trinitarianism.

The term “in us” undermines trinitarianism for a specific reason: John is saying that the Word “became flesh” by tenting “in us” — in God’s people! But that is not what trinitarians want. They prefer the non-literal “among us” in order to imply that the Word, by incarnation, became the person of Jesus Christ who now lives “among us,” that is, the Word became flesh in Jesus rather than “in us”.

The literal “in us” nullifies Jesus’ deity in John 1:1 and the God-man incarnation in 1:14 by denying the identification of the “Word” with Jesus Christ which is so central to trinitarian dogma.

We now present the biblical evidence for “in us” in seven points.

Point 1: In John, en almost never means “among”

The Greek word en occurs 474 times in John’s writings (226 times in his gospel, 90 times in his letters, 158 times in Revelation). The crucial question is this: How many of these 474 instances actually mean “among”? One way of arriving at an answer that is acceptable to trinitarians is for a trinitarian Bible such as NASB to do the “counting” for us via actual translation.

If you are willing to do the hard work by going through the 474 instances, here is the final tally: Of the 473 instances of en in John’s writings outside the disputed Jn.1:14, only 7 are translated as “among” by NASB (Jn.7:12; 9:16; 10:19; 11:54; 12:35; 15:24; Rev.2:1). Hence, even by NASB’s own reckoning, en almost never means “among” — a sense that occurs in only 1.5% of all instances of en.

By contrast, NASB translates en as “in” in over 95% of the instances. Hence the choice of “among us” over “in us” in John 1:14 appears to have been influenced by tradition.

Point 2: In John’s writings outside John 1:14, en hēmin always means “in us” and never “among us”

Instead of the single word en, what about the phrase en hēmin that we see in John 1:14? The exact and literal translation of this phrase is “in us” rather than “among us”.

Here is a crucial fact: In John’s writings outside the debated John 1:14, en hēmin always means “in us” and never “among us,” without exception! Hence the trinitarian rendering “among us” for John 1:14 is foreign to John’s understanding of en hēmin.

In John’s writings, en hēmin (“in us”) is consistent in meaning. To repeat: In his writings outside the debated John 1:14, en hēmin always means “in us” and never “among us,” without exception.

To give specific data: Outside John 1:14 en hēmin occurs ten times in John’s writings. Interestingly, NASB never translates the ten instances as “among us” but always as “in us”. An exception is 1John 4:16 where NASB has neither “in us” nor “among us”, but “for us”. But it is more likely to be “in us” (as in the NET Bible) because that is how NASB translates the other four instances of en hēmin in the very same chapter (vv.9,12, 12,13).

It is a straightforward exercise to verify that “among us” makes no sense in any of the following ten instances of en hēmin (all verses are quoted from NASB; note the words in boldface):

John 17:21 … even as You, Father, are in Me and I in You, that they also may be in Us …

1 John 1:8 If we say that we have no sin, we are deceiving ourselves and the truth is not in us.

1 John 1:10 If we say that we have not sinned, we make Him a liar and His word is not in us.

1 John 3:24 … We know by this that He abides in us, by the Spirit whom He has given us.

1 John 4:9 By this the love of God was manifested in us …

1 John 4:12 … if we love one another, God abides in us, and His love is perfected in us. [en hēmin occurs twice in this verse]

1 John 4:13 By this we know that we abide in Him and He in us, because He has given us of His Spirit.

1 John 4:16 We have come to know and have believed the love which God has for us … [more likely to be “in us” as we have mentioned]

2 John 1:2 for the sake of the truth which abides in us …

Point 3: In John’s writings, en hēmin often means “God dwells in us”

The word “abide” in the above verses will confuse some modern readers because NASB uses “abide” in the sense of “live” or “dwell,” which is an archaic meaning of “abide” (Oxford English Dictionary). But we gain insight when we read three of the verses from the more readable NIV (note the words in boldface):

1 John 3:24 The one who keeps God’s commands lives in him, and he in them. And this is how we know that he lives in us: We know it by the Spirit he gave us.

1 John 4:12 No one has ever seen God; but if we love one another, God lives in us and his love is made complete in us.

1 John 4:13 This is how we know that we live in him and he in us: He has given us of his Spirit.

In these three verses, the concept of God living in us comes out powerfully: “he lives in us” (3:24); “God lives in us” (4:12); “we live in him and he in us” (4:13). This strengthens the case for the literal translation “tented in us” in John 1:14, proving that “tented in us” is correct not only lexically and grammatically but also theologically for aligning with John’s concept of God living “in” His people.

Point 4: John distinguishes “in us” and “among us” by two Greek words in the space of 12 verses

To repeat: Outside the debated John 1:14, John never uses en hēmin to mean “among us” but always “in us,” without exception. That being the case, does John ever use a Greek word other than en to express “among us”? Yes he does, for just 12 verses later, in Jn.1:26, he records the following words by John the Baptist: “but among you stands one whom you do not know”. Here the Greek for “among” is mesos, which is different from en in John 1:14. Hence, within the space of 12 verses, John makes a distinction between “in” and “among” using two different words, en and mesos. There is no reason for the trinitarian conflation of “among us” and “in us” in John 1:14.

Point 5: The rendering “in us” for John 1:14 is known in church history

There is nothing novel or farfetched about the fact that en hēmin literally means “in us” rather than “among us”. This is an elementary fact of the Greek language. Ask anyone who knows some biblical Greek to translate en hēmin without showing him or her John 1:14, and he or she will immediately tell you “in us” without batting an eye.

In fact many famous people in church history from the early church to the present have taken John 1:14 to mean “in us”. Some examples:

Jerome (347-420), principal translator of the Latin Vulgate

Augustine (354-430), the most influential theologian of the Latin church

Theodore of Antioch (350-428), bishop of Mopsuestia, best known for his perceptive criticism of the allegorical method of Bible interpretation

John Wycliffe (1331-1384), Bible translator, whose Bible (the Wycliffe Bible) has a note on John 1:14 which says that “dwelled among us” is actually “dwelled in us”

George Fox (1624-1691), founder of the Quakers, who says en hēmin is often mistranslated as “among us” (he says it should be “in us”)

Allen D. Callahan, Baptist minister and Associate Professor of New Testament at Harvard University, in his book, A Love Supreme: A History of the Johannine Tradition (p.51)

Raymond E. Brown, one of the foremost New Testament scholars of the 20th century. In his acclaimed two-volume commentary on John’s gospel in the Anchor-Yale series (Yale University Press), Brown notes that in John 1:14, “among us” is literally “in us”.

The meaning “God in us” is seen often in Augustine’s writings, e.g., his exposition of Psalm 68. In his Confessions, he would speak of God dwelling in people: “For when I call on him I ask him to come into me. And what place is there in me into which my God can come? How could God, the God who made both heaven and earth, come into me?” (Confessions, Book 1, chapter 2)

Jerome is probably the greatest biblical scholar of the early church. The 29-volume Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture, in volume 4, says that “Jerome has generally been viewed as the finest scholar among the early church fathers and has been called the greatest biblical scholar ever produced in the history of the Latin church.”

Jerome is the main translator of the Vulgate (commonly known as the Latin Vulgate), a Latin Bible translated from the Greek and Hebrew sources available to him. In John 1:14, the Vulgate translates the Greek en hēmin as Latin in nobis (see the critical Latin text by the German Bible Society) which in secular contexts is often translated into English as “in us”. For example, in nobis is well known in English through est deus in nobis, a saying by the Roman poet Ovid which means “there is a god in us” or “there is a god within us”.

Point 6: John’s teaching that the Word “tented in us” aligns with Paul’s teaching that God dwells in us, the temple of God

John’s monumental declaration that the Word “tented in us” (the literal translation) aligns with Paul’s teaching that we are the temple in which God dwells. Paul’s teaching is seen in the following passages, all from the NET Bible; note the words in boldface:

Do you not know that you are God’s temple and that God’s Spirit dwells in you? (1Cor.3:16)

Or do you not know that your body is the temple of the Holy Spirit who is in you … ? (1Cor.6:19)

… Christ Jesus himself as the cornerstone. In him the whole building, being joined together, grows into a holy temple in the Lord, in whom you also are being built together into a dwelling place of God in the Spirit. (Eph.2:20-22)

These three passages combined have a total of 11 instances of “you” or “your,” all plural in the Greek. The plural brings out the corporateness of God’s people as the temple of God, with Christ as the “cornerstone” (Eph.2:20).

Note the parallel between Paul and John: Paul says that God dwells in us the temple of God, just as John 1:14 says that the Word (who is God) “tabernacled in us” (the literal translation of John 1:14).

Christ is the temple of God, and we too are the temple of God, yet there is only one temple: the temple of God whose cornerstone is Christ (to use the metaphor of a building), or equivalently a body whose head is Christ (to use the metaphor of a body).

Paul uses two equivalent metaphors: a building (the temple) and a body (the body of Christ). Just as there is one temple of God in the Old Testament, there is only one temple of God in the New Testament, or equivalently one body of Christ, the church (Eph.5:23; Col.1:18).

In the Old Testament, the tabernacle is not God Himself nor is it divine, but is God’s dwelling. Likewise, in the New Testament, the temple of God consisting of God’s people (with Christ as the head) is not God Himself nor is it divine, but is God’s dwelling filled with His glory (cf. Ex.40:34, “the glory of Yahweh filled the tabernacle”).

God’s glory shines most brightly in Jesus Christ, the cornerstone of the temple and the head of the body. Just as Paul speaks of the “glory of God in the face of Jesus Christ” (2Cor.4:6), so John says, “And we have seen his glory, glory as of the only Son from the Father, full of grace and truth” (Jn.1:14).

Point 7: God’s entire fullness dwells in Christ — and in us!

Finally, God’s entire fullness dwells in Christ:

For God was pleased to have all his fullness dwell in him (Col.1:19, NIV)

For in Christ all the fullness of the Deity lives in bodily form (Col.2:9, NIV)

Paul is saying that God’s entire fullness (Col.1:19) — indeed “all the fullness of the Deity” (2:9) — dwells in Christ “bodily”.

It will come as a shock to trinitarians that God’s entire fullness also dwells in God’s people, for Paul says: “that you may be filled with all the fullness of God” (Eph.3:19). In this verse, the word “you” is plural because “filled” is plural in the Greek. This brings out the corporateness of God’s people who as the dwelling place of God are filled with all His fullness. Indeed we are the “dwelling place of God in the Spirit” (Eph.2:22).

(c) 2021 Christian Disciples Church